This article is reserved for our subscribers

It’s hard to imagine that the landscape of Kébili, near Douz, at the gates of the Tunisian Sahara, is dotted with gas and oil wells. A protected wetland, the area is popular for its eerie landscape of pale salty water puddles set in the middle of the desert.

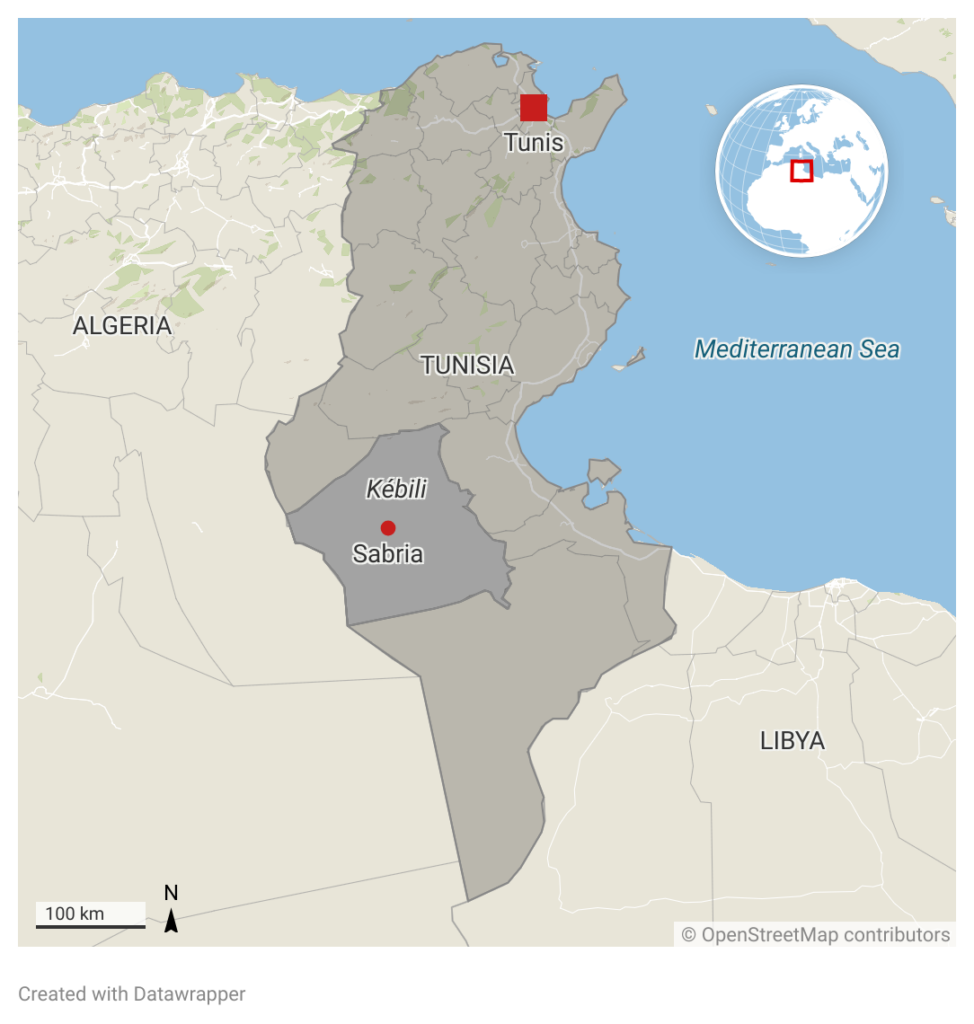

But it was here, in the Kébili region, that the sites of the Jersey-based French oil companies Perenco and Serinus were confronted in 2017 with repeated strikes and sit-ins organised by local civil society, which has been calling for better social and environmental monitoring of the two foreign companies operating in Tunisia since 2012.

The protest led to the signing of a 114-point agreement with civil society groups. But the extraction sites were classified as “military zones”, which prevented any attempt at protest – or indeed at monitoring the activities of oil and gas companies.

After Perenco, which was taken to court in France in November 2022 by the associations Sherpa and Friends of the Earth for the pollution caused by its activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it is now the turn of the company Serinus.

Registered in Jersey (an island between the UK and France, considered by some countries to be a tax haven), the company controls Winstar, the Tunisian operator responsible for exploiting the Sabria oil field in Kébili, whose extraction practices are equally dubious.

A “small company” owned by a Polish energy giant

The fracking technique involves injecting water, mixed with hundreds of toxic additives, at very high pressure. This chemical solution can cause serious pollution of any groundwater layers that may be intersected by the drilling process.

Such operations can also affect local seismic activity. This is due to the depth of the targeted oil reservoirs, which can be located more than 3000m underground.

Fracking has been the subject of heated debate in Tunisia for years. In 2012 the giant Shell was forced to abandon plans to drill 742 shale wells in Kairouan after a wave of local protests.

The practice has long been associated with shale extraction, but it is also used to extract so-called “compact” oil and gas reservoirs just a few metres away from shale-rich source rocks. This “unconventional hydrocarbon” is less familiar to the public than shale gas.

The extraction processes for shale deposits are very similar to those for compact deposits, both in terms of technology and the environmental risks involved. In Tunisia, this linguistic subtlety and the absence of legal definitions are bound to benefit oil and gas operators.

The term “well stimulation jobs”, rather than fracking, is a way of avoiding controversy. But the extraction process is as unconventional as that used for shale gas.

Fracking and unconventional exploitation

Compact oil and gas has less worrying connotations for the critics of ETAP and its partners. “Semi-conventional” resources are preferred to unconventional ones, and fracking jobs have been rebranded by Winstar Tunisia (the local operator) as “stimulation projects”.

However, according to a senior petroleum engineer who wishes to remain anonymous: “There is no such thing as semi-conventional. There is conventional and there is unconventional. The mere use of hydraulic fracturing is enough to qualify these fields as unconventional.”

A former director of Serinus insists of the Sabria concession: “Yes, this concession can be described as ‘semi-conventional’.” This is a category of hydrocarbons that, like shale, is not defined by law but has already been approved by the Tunisian government.

An online post by a former ETAP employee on the professional social network Linkedin in 2020 was clear about this: “Hydraulic fracturing on semi-conventional oil has already been approved”.

As for Serinus Energy, one engineer claimed to have carried out fracking work on behalf of Winstar. When contacted by email, the engineer refused to give the exact geographical coordinates of the sites where these operations were carried out.

However, a 2014 report by Winstar, entitled “Workover and stimulation operations by hydraulic fracturing on conventional reservoirs”, points to impact studies carried out further south in the Tunisian Sahara, on the “Ech-Chouech” concession.

When contacted by our journalists, Serinus Energy confirmed that hydraulic fracturing had indeed been carried out on its Ech-Chouech concession, but not on the Sabria site. Here, according to the company, the reservoirs are “conventional”. This view is shared by the EBRD, which was contacted by email.

Receive the best of European journalism straight to your inbox every Thursday

Serinus also says it distinguishes these operations, which have been “commonplace since the 1960s”, from “more modern practices associated with shale and unconventional resource extraction”.

As far as the EBRD is concerned, the Serinus project is encompassed by the Society of Petroleum Engineers’ definitions for conventional resources.

However, there exist many definitions of “unconventional”. For the US Environmental Protection Agency, the mere use of hydraulic fracturing – as was the case for Serinus – is enough to qualify an operation as “unconventional”.

Serinus also points out that these fracturing operations were carried out using the company’s own funds, not the EBRD loan.

Fracking “anti-constitutional”

Winstar Tunisia has had an interest in unconventional hydrocarbons since at least 2010. In the absence of any regulatory framework surrounding the practice, the company announced the development of two experimental wells for shale resources that year and in 2011. But the depth of the wells (over 3,000 metres) and the geological layer targeted prove it: these are not just “unconventional” wells; they are shale plays.

According to Afef Hammami-Marrakchi, a lecturer at the University of Law in Sfax, Tunisia’s hydrocarbon code does not yet provide a legal framework for the management of this type of energy resource.

Even then, the use of environmentally harmful extraction techniques – such as fracking or shale exploration – should have been subject to parliamentary debate, as stipulated in Article 13 of the 2014 Tunisian Constitution. This provision was omitted from the new constitution promulgated by Tunisian president Kaïs Saïed in 2022.

Serinus’s neighbour in the Sabria field, the company Perenco, used the legal void to engage in similar practices in the El Farouar and Djebil National Park regions, as revealed by Jeune Afrique in 2022.

In 2017, the Tunisian government commissioned a study on the legal and technical possibilities of unconventional extraction from the Canadian company WSP Global and the Tunisian SCET. But despite an estimated cost of 2.7 billion Tunisian dinars, the study never saw the light of day, leaving the issue in limbo.

Gas flaring and expired hydrocarbon licences

During our reporting, we also discovered gas flares at the Sabria site, placed horizontally in a sand pit, as in the photo below. This is another practice that is not regulated by the Tunisian Hydrocarbon Code.

Flaring is the process of burning off unwanted methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

The company is also in legal limbo over two sites it continues to own even though their licences have expired. According to Hydrocarbon Secrets, a guide published in 2019, the Sanghar concession – which is 100% owned by Serinus through its Tunisian subsidiary Winstar – expired in December 2021 and the site has not been in production since 2016.

The Tunisian energy ministry has made no official declaration on the subject and has not asked the company to reimburse the amount spent on decommissioning the site and restoring it to its original state, as required by the Hydrocarbons Code.

In a forthcoming version of the Hydrocarbon Secrets, which we were able to consult before its publication, it is revealed that the same problem remains with regard to the Chouch concession. There too the operator is supposed to reimburse the closure costs and ensure rehabilitation.

The guide also mentions that failure to plug the wells could lead to a natural disaster in the event of an oil or gas spill.

The Serinus-Kulczyk connection

In its assessment of Serinus Energy’s funded projects, the EBRD states that the company has repaid almost 93% of its loan, while the remaining part has been converted into shares in the company for the benefit of the EBRD, to the value of $3.5 million.

The EBRD has not yet replied to our questions. However, Serinus Energy told us that as part of its capital restructuring, the equivalent of 9.9% of its shares held by the investment bank had been sold to unidentified buyers in 2022.

In 2021, the same year the project was completed (and negatively assessed), Kulczyk Investments sold all of its shares in Serinus Energy, which had since relocated to the tax haven of Jersey.

The company’s shareholders now include more than twenty companies, including investment fund Quercus TFI and online gambling specialist Spreadex Limited. The latter was fined almost €1.3 million by the UK Gambling Commission last year for failing to meet its corporate social responsibility obligations.

Serinus Energy is still run by Lukas Radziniak, a former Polish deputy justice minister (2007-2009) and a close “lieutenant” of the Kulczyk clan, through the various companies and investment funds he still manages. These include Kulczyk Investments, the former owner of Serinus Energy.