John Dunford sat at the back of the church, listening to the eulogy.

Oh, how he hated the deceased.

Already a Subscriber? Sign in

Dr. James Anderson gave this old typewriter of his to John Dunford as a gift.

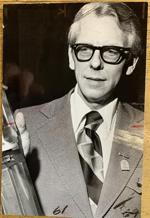

This photo of Dr. James Anderson (that includes editing markings) was published in The Hamilton Spectator in 1975, when he was named Citizen of the Year, in part for his Cool School initiative, and work with teens with drug abuse issues.

Teenage John Dunford, when he worked at McDonald’s in Nova Scotia, soon before he moved back to Hamilton to attend Cool School, an alternative education program for teens founded by Dr. James Anderson.

John Dunford says this was Dr. James Anderson’s home, at Herkimer and Bay Street South.

The letter written by Dr. James Anderson recommending John Dunford be accepted to university based on his Cool School performance.

John Dunford is pictured recently at his west Hamilton home. Dunford has filed a $2.8-million lawsuit against Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS), arguing that HHS should be liable for two alleged sexual assaults by Dr. James Anderson against him in February 1983, when Dunford was a student of Anderson’s at Cool School, an alternative education program for teens. Anderson died in 1995.

Hamilton Spectator obituary story about the death of Dr. James Anderson in 1995.

Portrait of John Dunford painted by Hamilton artist Laurie Kallis, who dated Dunford in the early 2000s.