Leon Robert Blais’ hands shake as he pulls a .45-calibre semi-automatic handgun out of his backpack.

He fires into the air, a warning for everyone to stay back. The look on his face is hard, but his hands shake so much he has to put the gun on the ground, so he can rummage in his backpack for the key he’s taken.

Already a Subscriber? Sign in

The Sept. 23, 1995, headline in The Spectator about Leon Blais reads: “‘Bad kid’ behind breakout only 15.”

Standing with police

Leon Blais stands outside St. Patrick Roman Catholic Church in downtown Hamilton where on Fridays the De Mazenod Door Outreach hands out more than 500 meals a day to Hamilton’s most needy. Many in the line have known Blais for decades, both from his life of crime and his life of addiction that followed.

Sgt. Pete Wiesner, who leads a team of police that works with vulnerable people to connect them with resources and divert them away from the criminal justice system, has witnessed a transformation in career criminal Leon Blais and now counts himself as an ally.

Leon Blais first came to St. Patrick church high on crystal meth and in need of a meal. Later he started volunteering. That turned into a full-time job, where today he can be found doing everything from picking up food deliveries, to mowing the lawn. His dog Christina is always with him.

Father Tony O’Dell, who calls Leon Blais “my greatest success in many ways,” says Blais is trusted by the guests of St. Patrick church.

Addicts and Mob hitmen

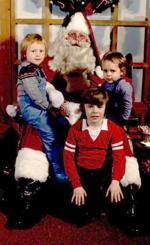

Leon Blais, right, was born in May 1980, the second of four boys, to Kathryn and Leon Blais.

A childhood photo shows Leon Blais with his brothers at Christmas.

The first arrest

As a teen, Leon Blais could not be named because he was a young offender. As his notoriety grew, The Spectator gave him the nickname Rudy.

A police shooting

Life changing toke

Leon Blais got his start volunteering at St. Patrick church by picking up trash.

The baptism

While Leon Blais was initially resistant to becoming a parishioner at St. Patrick church, that changed too. After being drawn in by the music, he found faith.

Leon Blais is seen here packing up bagged lunches for the De Mazenod Door Outreach. Last year, they served 122,000 meals and now they’re serving 500-plus meals a day.

Chalk butterflies

Leon Blais turned an interest in chalk art into an entire program, including art classes once a month at the ministry’s gift-shop, humankind: Gifts That Matter.