When Gillian Bennett ended her own life in 2014, MAID didn’t exist. Jonathan Francis Bennett died peacefully at his home on March 31 surrounded by a MAID team.

Article content

Jonathan Francis Bennett died peacefully at his home on Bowen Island on Sunday, March 31, at age 94, almost 10 years after his wife Gillian died.

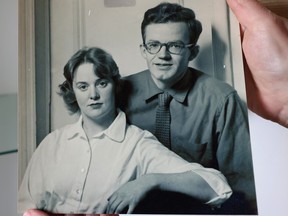

The couple had shared everything for over six decades. A love story that began when they toiled at a bread factory as young students in New Zealand. A move to the U.K. after Bennett’s acceptance to Oxford. Marriage, two children, six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. And thriving careers — he was a philosopher, teacher and translator, and she a clinical psychotherapist.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

Their deaths were strikingly different.

After a dementia diagnosis in her early 80s, Gillian discovered she had no legal right to end her life. So she dragged a mattress outside, lay down beside a beloved rocky bluff near their Bowen Island home and ingested Nembutal obtained on the black market.

“My brother and I couldn’t be with her, or we could have been charged with aiding and abetting a suicide, or even murder,” said their daughter, Sara Bennett-Fox.

Last Sunday, Jonathan died comfortably in his favourite recliner inside his home. Sara held one hand, his son Guy held the other. Also present was a medical-assistance-in-dying team. They asked Jonathan if he knew what was happening.

He said yes, he knew where he was and that he was about to receive MAID.

“He was very clear that he was ready,” said Sara.

The nurse placed an IV in his arm, and the physician explained the process step-by-step.

They would give three drugs in order. The first one would work in a minute, and he would fall asleep. The second one would put him in a coma. The third drug would stop his breathing.

The MAID team positioned themselves behind the recliner so the last faces Jonathan saw would be those of his children.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

“It was so kind, so gentle and so respectful,” said Sara. “He died with a doctor present, a doctor he had met with at least four times. No one worried that something would go dreadfully wrong.”

When her mother ended her own life in 2014, MAID didn’t exist.

Gillian, who had been struggling with dementia for several years, didn’t want to lose her brilliant mind or languish in a care home. She did some research and went underground to obtain the medication to end her life.

The family was supportive of her wishes — as supportive as they could be, but also terrified of what might go wrong, said Sara.

Was the medication she had sourced through the euthanasia underground reliable? Could it fail? What if she was left injured or in pain?

“It could have been a street drug for all we knew,” said Sara. “It could have been awful, and left her worse off than she was before.”

The secrecy, the risk, the spectre of a criminal investigation and the cruelty of not being able to have family present was something the couple never wanted anyone else to endure.

Gillian left behind a website, deadatnoon.com, with a letter that expressed her final wish of igniting a conversation about medical assistance in dying.

Advertisement 4

Article content

After a Postmedia News story on her death, the website received hundreds of thousands of views.

“We stopped counting at 500,000,” said her grandson, Quentin Bennett-Fox.

Letters came from around the world.

“We were so afraid people would be cruel,” said Sara. “It was the opposite. We had so much support. It was really profound.”

The family received some solace: No criminal charges were laid against Jonathan, who had held his wife’s hand as she died, and then reported the matter to the police. A subsequent autopsy revealed the drug she had sourced from strangers on the internet was indeed what she had ordered. She would have felt no pain.

Even more important, the conversation Gillian had hoped to prompt began to move from kitchen tables to Parliament.

At the time Gillian died in 2014, a years-long legal challenge from the right-to-die movement was slowly making its way through the courts. In February 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada released Carter v. Canada, a decision that would be a turning point about the law on assisted dying.

The decision found that the Criminal Code provisions that made it a crime to help a person end their life violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In 2016, the Criminal Code was amended and federal legislation was passed to allow MAID for adults in certain circumstances.

Advertisement 5

Article content

“My mom’s legacy, what she wanted, was to help regular families to have the conversation about death and dying. There are so many taboos around that, taboos that are not helpful,” said Sara.

“MAID doesn’t take away any of the pain of the loss. We have cried so many tears in the last few days. But it makes it about honouring their wishes and who they were.”

After Gillian died, Jonathan continued to find purpose in his work, his landscaping, building pathways and trails, his rose garden, friends and family, but after health challenges, including cancer, and several serious falls he had become increasingly frail and was living with chronic pain.

Jonathan’s last months were filled with the small pleasures of work, friends and family, and sometimes a rose Sara would place on his desk. Just 10 days before he died, he finished and published a final translation of Francis Bacon for his popular philosophy website earlymoderntexts.com.

“He set the date for when he was going to die. He was completely at peace,” said Sara.

Despite the stark differences in how their lives ended, they were also, in a way, similar. They each chose the time and date of their ending. They each died on Bowen Island. Each was encouraged by the strength and fortitude of the other.

Advertisement 6

Article content

“My dad was so proud of my mom’s legacy, so proud that she had that victory,” said Sara.

Jonathan Bennett’s good death was a gift of that legacy.

Recommended from Editorial

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the news you need to know — add VancouverSun.com and TheProvince.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

You can also support our journalism by becoming a digital subscriber: For just $14 a month, you can get unlimited access to The Vancouver Sun, The Province, National Post and 13 other Canadian news sites. Support us by subscribing today: The Vancouver Sun | The Province.

Article content